Starting your brewery on sound footing

By Erik Lars Myers

One of the biggest challenges a new brewery owner has when starting up seems like the simplest question of all: What size brewery am I starting?

There’s no fool-proof method to get this crystal ball prediction perfectly correct, but a commonsense approach can help target the outcome so that you can plan your investments wisely.

The first decision begins with determining the size of your market. Ask yourself: Are you in a small town or a big city? Are you in a location that people can walk to, or do they have to drive? Do you have parking space? How much? How many seats do you have in your establishment? How many hours are you open? Are you distributing your product in kegs? Cans? Bottles? How many distribution customers exist within a half-hour drive of your location? How many of those will realistically put one new beer on tap?

There are no easy answers or simple math, but going through those questions can give you the first gut check: Realistically – is this a relatively small operation serving your own neighborhood? Or are you building a manufacturing plant with plans to service a large metro area?

When in doubt, don’t be afraid to undershoot a little. While you want to be able to make enough product to cover cost of goods, overhead and debt service, having to increase capacity because you have a high demand and great sales is a much easier – and nicer – problem to solve than having too much product or, worse, old product moving into the market because your brewing capacity and inventory outstrips demand. This is 2026, and we’re no longer in a market in which “if you brew it, they will drink.”

However, be wary of 1- to 2-barrel operations which put a high demand on factory time without creating a reasonable amount of product. Making one barrel of beer takes roughly the same amount of work as making ten barrels of beer or thirty barrels of beer. The difference is economy of scale. For any commercial operation, even an exceedingly small one, be wary of anything smaller than five barrels.

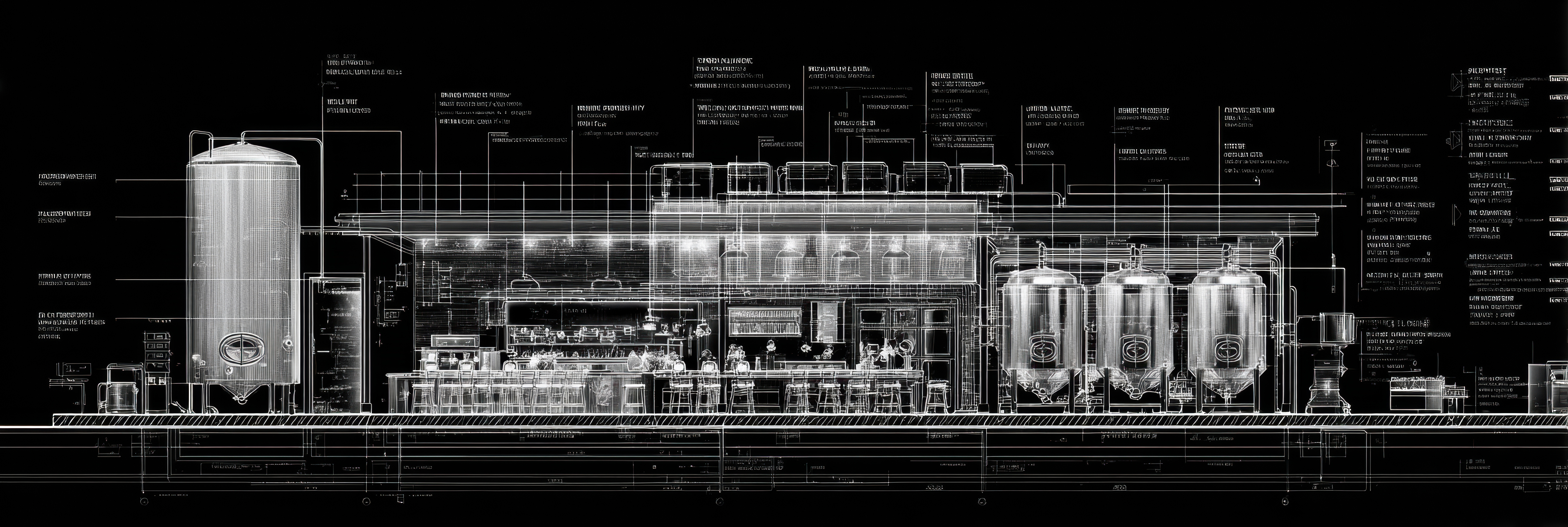

Once you determine your relative market demand, the first limiting factor you must consider is the size of your production floor. As a rule of thumb, the maximum yearly capacity of your brewery will equal one barrel per square foot of floor space. For example, if you have a building which – after offices, storage space, loading dock, and forklift parking – has roughly 2,000 square feet of space dedicated to your production floor (brewery, cellar, packaging), the most you’ll be able to get out of that space is approximately 2,000 barrels per year. Note! You will definitely make less than that, but over time you probably won’t squeeze out more.

Next, it’s time to figure out the balance of system size to production space and what you’re planning to offer. If you intend to sell a couple of solid and consistent offerings in a planned distribution, you can lean towards a larger system that will allow you to make a higher volume of those few offerings while brewing less frequently. If you are planning a wide slate of varietal, seasonal beers – or less traditional beers with experimental ingredients – consider a smaller system with higher turn capacity.

In today’s market, shooting smaller is not necessarily a bad idea. The difference between a 7-barrel brewhouse and a 15-barrel brewhouse can be measured in hours. In other words, a 7-barrel brewhouse can be used to create 15 barrels of the same beer but it will take twice as long on the brew deck to do it. On the other hand, the difference between a 15-barrel brewhouse and a 7-barrel brewhouse can be measured in days. As in, the number of days you will have stock to sell from a 15 barrel batch is twice that of a 7-barrel batch.

Unless you are the only game in town, incredibly lucky, or exceptionally good, sales will be your largest production bottleneck. When it comes to figuring out how many fermenters and brite tanks to purchase, and what size, start by looking back over all the other decisions and considering turn time.

On average, a good rule of thumb is approximately 16 – 18 days between a beer being brewed and it being ready for market. That is one day in the brewhouse, 10 – 14 days in the fermenter including cold crashing, 1 – 2 days in a brite tank, and 1 – 2 days for packaging. That timeline can be extended for lagers by a few days or a few weeks.

Can beer be produced faster than that? Without question. But as a rule of thumb, at start up, plan to take your time. Give yourself time to get it right.

Now take a moment to revisit the idea of throughput and your market size and how quickly you might move through product.

1 barrel of beer = 31 gallons = 2 half barrel kegs = 6 sixth barrel kegs = ~240 pints.

With a 15-barrel brewhouse every batch would produce

465 gallons OR 30 half barrel kegs OR 90 sixth barrel or most realistically a combination thereof. All that equals 3600 pints of one sole product.

In a regular taproom setting you can expect to sell, on average, 1.5 to 2 beers per customer on a visit. In a 150-seat taproom at maximum capacity, if all the seats turn over twice per night you can expect to sell approximately 300 pints, or just over 1 barrel of beer. Over the course of any given week, in a high-volume taproom, you should aim to turn over a minimum of 1 turn of your brewhouse in a 1-week period. In other words, plan to brew at least once per week, on average, to begin with. Again – as you grow, you can always add more brew days and more fermenters.

It is also good to remember that the numbers of beers that you offer will not correspond to a higher volume of sales, but rather it will spread those sales across a wider number of products with the largest volume concentrated on 2 – 3 beers, probably your IPAs and Pilsener (or Pilsener analog). To put this another way: if you have 6 beers on tap or 12 beers on tap, you will still sell the roughly same amount of beer per week, but all of the beers will move more slowly, with the possible exception of your fastest selling beers.

This all means that a mix of fermenter and brite sizes can be helpful when planning capacity. A mix of fermenters that match your brewhouse size and fermenters that are double your brewhouse size is a good idea. Double-batch your high-volume beers and single-batch your slower moving offerings to manage inventory well. If something turns into a high-volume beer, you can always make more. If something is moving slowly, there’s nothing worse than having so much that it isn’t just unpopular, but also old and stale.

If you are brewing at least once per week and have a 16-day turn on your fermenters, then you should have a minimum of 4 fermenters. However, give yourself room to get ahead of inventory and take your time with beer, or the option to make more of your high-volume beers. An easy recommendation is 4 fermenters that match your brewhouse size and 2 fermenters that are twice your brewhouse size. Thus, a startup with a 5-barrel brewhouse might start with four 5-barrel fermenters and two 10-barrel fermenters.

Since turn time in a brite tank is much smaller than in a fermenter, you need fewer brites. You will want one brite tank for every 3 – 4 fermenters of any give size. In this scenario, two 5-barrel brites and one 10-barrel brite would be sufficient. At a 16-day turn on each fermenter (a little under two turns per month) that gives you an initial maximum brewing capacity of approximately 700 barrels per year, depending on fermentation efficiency, work weeks, holidays, and sales. Your final volume for the year will almost certainly be less than that.

Finally, the last piece to consider is cooperage. Kegs are one of the highest cost, highest value assets in your operation and are often overlooked. To begin with, if you are only providing beer to your own taproom and you are not using serving tanks, you need enough cooperage to hold all your volume in inventory… and then some. For every individual product you offer you will need empty kegs waiting to be filled, kegs filled with beer waiting to go on tap or be sold, kegs on tap, and empty/dirty kegs waiting to be cleaned. If you are in distribution you will need to add two more scenarios: kegs at the customer waiting to go on tap and empty kegs at the customer waiting to be picked up. You will also lose a small percentage of your kegs each year in the marketplace as they get lost or stolen.

For each 5-barrel batch of beer, you need the equivalent volume of 20 – 30 barrels in cooperage. Half-barrel kegs (120 pints) are much more efficient but take up much more space and are clumsy to work with. They also typically sell at a lower price per pint than alternatives. Sixth-barrel kegs (40 pints), or sixtels, are much easier to work with and allow for more variety but are much less efficient on the production floor. You will probably maintain an inventory of both halves and sixtels at roughly an equivalent internal volume. For each half barrel keg, keep three sixth barrel kegs. For a 5-barrel startup brewery offering four distinct brands out of the gate, with limited distribution, starting with 100 half-barrel kegs and 300 sixth-barrel kegs would not be out of line.

Of course, if there is a plan to do packaging in other formats (bottles or cans) that reduces the need for cooperage, so plan accordingly. It is better to have more kegs than you need and have the luxury of cleaning them when you can – remember, each keg takes three minutes minimum on the keg washer – than to have too few kegs and not be able to package beer or brew because you are short on cooperage and have nowhere to put ready product.

There is no perfect answer to what equipment you will need in a startup scenario – every brewery, location, taproom, and distribution model will create diverse needs, but a good examination of these points can start you off on the right foot. Breweries are expensive, particularly at initial stages, but it is worth the money to have the right assets in place rather than to spend the life of your business trying to catch up.